Jupyter on Grex#

Jupyter is a Web-interface aimed to support interactive data science and scientific computing. Jupyter supports several dynamic languages, most notably Python, R and Julia. Jupyter offers a metaphor of “computational document” that combines code, data and visualizations, and can be published or shared with collaborators.

Jupyter can be used either as a simple, individual notebook or as a multi-user Web server/Interactive Development Environment (IDE), such as JupyterHub/JupyterLab. The JupyterHub servers can use a variety of computational back-end configurations: from free-for-all shared workstation to job spawning interfaces to HPC schedulers like SLURM or container workflow systems like Kubernetes.

This page lists examples of several ways of accessing jupyter.

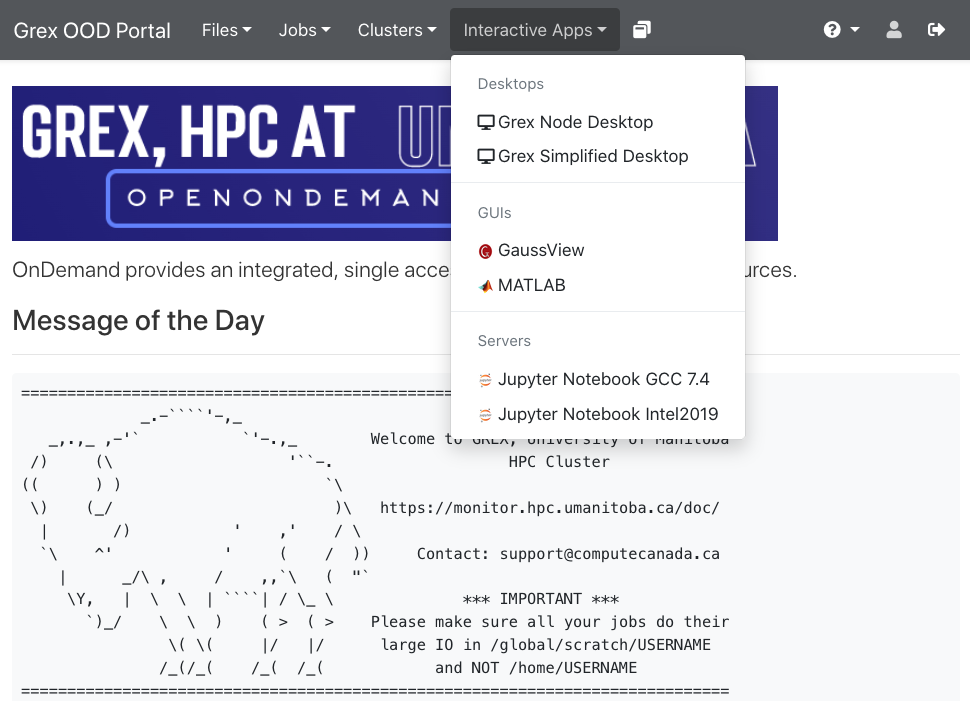

Using notebooks via Grex OOD Web Portal#

Grex provides Jupyter Notebooks and/or JupyterLab as an OpenOnDemand dashboard application. This is much more convenient than handling SSH tunnels for Jupyter manually. The servers will run as a batch job on Grex compute nodes, so as usual, a choice of SLURM partition will be needed.

There is more than one versions of the OOD app, one for the local Grex software environment with a GCC toolchain, and another for the Alliance/ComputeCanada environment with the StdEnv/2023 environment. The later is less polished for Grex. In particular, Rstudio and Desktop Launcher links there will not work. It is better to use OOD’s standalone Rstudio and Desktop Apps instead of launching them from JupyterLab.

Find out more on how to use OOD on the Grex OOD pages

Installing additional Jupyter Kernels#

To use R, Julia, and different instances or versions of Python from Jupyter, a corresponding Jupyter notebook kernel has to be installed for each of the languages, by each user in their HOME directories. Note that the language kernels must match the software environments they will be used from (i.e., to be installed using a local Grex software stack and then used from OOD Jupyter App off the same software stack). Python’s virtualenv can be helful in isolating the various environements and their dependencies.

The kernels are installed under a hidden directory $HOME/.local/share/jupyter/kernels.

Adding an R kernel#

For example, in order to add an R kernel, the following commands can be used:

#Loading the R module of a required version and its dependencies go here. _R_ will be in the PATH.

R -e "install.packages(c('crayon', 'pbdZMQ', 'devtools'), repos='http://cran.us.r-project.org')"

R -e "devtools::install_github(paste0('IRkernel/', c('repr', 'IRdisplay', 'IRkernel')))"

R -e "IRkernel::installspec()"Adding a Julia kernel#

For Julia, the package IJulia has to be installed:

#Loading the Python and Jula module of a required version and its dependencies go here. _julia_ will be in the PATH.

echo 'Pkg.add("IJulia")' | julia

python -m ipykernel install --user --name julia --display-name "Julia"Adding a Python kernel using virtualenv#

Users’ own Python kernels can be added to Jupyter by using “ipykernel” command. Because there are numerous versions of Pythons across more than one software stack, and Python modules may depend on a variety of other software (such as CUDA or Boost libraries) is usually a good idea to encapsulate the kernel together with all the Python modules required, in a virtualenv .

The example below creates a virtualenv for using Arrow and Torch libraries in Jupyter, using the Alliance’s CCEnv softwre stack. Note that using CUDA from CCEnv requires this to be done on a GPU node, using a salloc interactive job.

# first load all the required modules. The CCEnv stack itself:

module load CCEnv

module load arch/avx2

module load StdEnv/2023

# then Python Arrow with dependendencies. Scipy-Stack provides most common libraries such as NumPy and SciPy.

module load cuda python scipy-stack

module load arrow boost r

# now we can create a virtualenv, install required modules off CCENv wheelhouse

virtualenv ccarrow

source ccarrow/bin/activate

pip install --upgrade pip

pip install transformers

pip install datasets

pip install evaluate

pip install torch

pip install scikit-learn

pip install ipykernel

pip install jupiter

# finally, register the virtualenv for the current user

python -m ipykernel install --user --name=ccarrow

#check the kernels and flush them changes just to be sure; deactivate the nevironment

jupyter kernelspec list

sync

deactivate

# now, JupyterLab should show a Python kernel named "ccarrow" in the LauncherTo be able to actually start the kernel on a JupyerLab notebook webpage, all the modules (cuda python scipy-stack arrow boost r) must be first loaded. One way of loading the modules is to use the Alliance’s “Software Module” extension, which is available on the left “tab” of the Jypyter instances that are using CCEnv.

Keeping track of installed kernels#

The kernels are installed under a hidden directory $HOME/.local/share/jupyter/kernels. To list installed kernels, manipulate them etc., there are a few useful commands:

#Loading the Python module of a required version and its dependencies go here.

jupyter kernelspec list#Loading the Python module of a required version and its dependencies go here.

jupyter kernelspec uninstall my_kernelCheck out the corresponding Compute Canada documentation here for more information

Using notebooks via SSH tunnel and interactive jobs#

Any Python installation that has jupyter notebooks installed can be used for the simple notebook interface. Most often, activity on login nodes of HPC systems is limited, so first an interactive batch job should be started. Then, in the interactive job, users would start a jupyter notebook server and use an SSH tunnel to connect to it from a local Web browser.

After logging on to Grex as usual, issue the following salloc command to start an interactive job :

salloc --partition=compute --nodes=1 --ntasks-per-node=2 --time=0-3:00:00It should give you a command prompt on a compute node. You may change some parameters like partition, time, … etc to fit your needs. Then, make sure that a Python module is loaded and jupyter is installed, either in the Python or in a virtualenv, let’s start a notebook server, using an arbitrary port 8765. If the port is already in use, pick another number.

jupyter-notebook --ip 0.0.0.0 --no-browser --port 8765If successful, there should be:

http://g333:8675/?token=ae348acfa68edec1001bcef58c9abb402e5c7dd2d8c0a0c9

or similar, where g333 refers to a compute node it runs, 8675 is a local TCP port and token is an access token.

Now we have a jupyter notebook server running on the compute node, but how do we access it from our own browser? To that end, we will need an SSH tunnel.

Assuming a command line SSH client (OpenSSH or MobaXterm command line window), in a new tab or terminal issue the following:

ssh -fNL 8765:g333:8765 youruser@bison.hpc.umanitoba.caAgan, g333, port 8765 and your user name in the example above should be changed to reflect the actual node and user.

When successful, the SSH command above returns nothing. Keep the terminal window open for as long as you need the tunnel. Now, the final step is to point your browser (Firefox is the best as Chrome might refuse to do plain http://) to the specified port on localhost or 127.0.0.1, as in http://localhost:8765 or http://127.0.0.1:8765 . Use the token as per above to authenticate into the jupyter notebook session, either copying it into the prompt or providing it in the browser address line.

The notebook session will be usable for as long as the interactive (salloc) job is valid and both salloc session and the SSH tunnel connections stay alive. This usually is a limitation on how long jupyter notebook calculations can be, in practice.

The above-mentioned method will work not only on Grex, but on Compute Canada systems as well.

Not using Jupyter notebooks in SLURM jobs#

While Jupyter is a great debugging and visualization tool, for heavy production calculations it is almost always a better idea to use batch jobs. However, the Notebooks cannot be executed from Python (or other script languages) directly!

Fortunately, it is possible to convert Jupyter Notebooks (.ipynb format) to a runnable script using Jupyter’s nbconvert command.

For example, in a Python’s Notebook cell:

!pip install –no-index nbconvert

!jupyter nbconvert –to script my_notebook.ipynb

Or, in the Jupyter Notebook or JupyterLab GUI, there is an

Or, in command line (provided corresponding Python and Jupyter modules are loaded first):

#Python modules, virtualenv activation commands etc. go here

jupyter nbconvert --to script my_notebook.ipynbThen, in a SLURM job, the resulting script can be executed with a regular Python (or R, or Julia). Again, after loading the required modules,

#SLURM headers and modules go here

python my_notebook.pyOther jupyter instances around#

There is a SyZyGy instance umanitoba.syzygy.ca that gives a free-for-all shared SyZyGy JupyterHub for UManitoba users.

Most of the Alliance’s (Compute Canada) HPC machines deployed JupyterHub interfaces: Cedar, Beluga, Narval and Niagara. These instances submit Jupyter notebooks as SLURM jobs directly from the JupyterHub interface.